KABUL, Afghanistan – For almost 15 months, the international community – not to mention Afghans themselves – has been up in arms over the ban on girls’ education in public schools across most provinces. But beyond education, women’s lives have transformed in many more ways than one since the U.S-back government crumbled, and the Emirate took control of the Presidential Palace in the late summer of 2021.

While many women continue to work in private sector jobs, women have disappeared from their once esteemed government occupations – except for a few female security checkers stationed in curtained rooms outside government buildings.

Multiple Taliban representatives tell me that women who held public sector jobs previously continue to receive a salary. But, as one official puts it, “they are paid to be at home servicing their husbands.”

Another Taliban voice, Abdul Hamid Jahadyar – the Spokesperson for the Ministry of Justice – asserts that during the Republic time, “women were being used as tools and not respected as humans.”

“Men should come every day to work. Then, from eight to four, a man receives a salary. But for women, there is a kind of mercy that they can get their salary at home without getting tired and having to pay for a taxi or anything,” he surmises. “They can stay at home as a spiritual person and get the salaries.”

We in the West often see and fixate on the big things that have changed for women, like jobs and education. Yet it is also the small things that offer a jarring glimpse into the dramatic transformations of everyday life.

For example, one Friday afternoon, the only weekend day in Afghanistan, I want to go horse riding at Kabul’s popular Qargha Lake Park – a recreational activity that wouldn’t have been a big deal in the former Republic times. Nevertheless, with a heavy Taliban presence enjoying the leisurely fruits of their day off, the boys guiding around the weathered horses fearfully whisper that I cannot go for a gallop. (One young horse owner eventually agrees to let me ride on the far side of the lake, out of view of any Taliban observers).

Moreover, it is also in the small acts of defiance, the ones that catch my enchanted western eye, that young Afghan women seem to clock up perhaps their most valued moral victories.

On another Friday at Qargha, Afghans of all ages float through the still waters in brightly-colored boats with long, elegant swan necks.

“I will have my fun,” one young woman says with a defiant curse word as she steps into a boat while throngs of Taliban operatives patrol the area.

Beauty salons have re-opened, albeit with the faces of both women and men typically painted over with a blob of dark paint or eyes haphazardly scratched out. Most women wear the same dress and hijab they always wore, defying Taliban advice (or mandate, depending on which Talib you talk too) to fully cover their faces.

I still see small groups of young women enjoying a night out together in the family section of a café, giggling and enjoying the tobacco water pipe known as Shisha. Occasionally, I spot a young woman behind the wheel of her car, but that doesn’t come without some risk of confrontation. One morning, I was stopped by an angry Talib at a checkpoint for daring to sit in the front seat. Another time while I was sick and sleeping, a concerned Talib accused my male driver and fixer of drugging and kidnapping me.

Of course, there are the big things too.

At least once a week in Kabul, gunshots crack the air. It is usually a sign that women are out in the streets protesting again, and the Taliban foot soldiers have been dispatched to disperse the gathering with a heavy hand. The reasons for the demonstrations are varied. Sometimes it is the fight for education and equal rights; other times, it is to support minorities like the Hazara or to show solidarity with the dissidents rallying against the regime in neighboring Iran.

One day I meet Assia in a restaurant garden. She is 23, attends almost every protest, hails from Panjshir province and is the sort of woman who refuses to go quietly into exile. She calls the cadre of protestors “a union” made up of politicians, civil society activists, and students whom all come under one umbrella and organize their marches on social media.

Assia used to study computer science at the university but lost her job after the Taliban return, which meant she could no longer afford the tuition fees. Now, her daily life is dedicated to activism. I ask her why more men don’t attend the demonstrations in support of women, as the photos I see are almost entirely of women with signs and singing out slogans.

“There are three types of Afghan men. One group has similar beliefs to what the Taliban has. Then there is a second group that remembers what it was like under the first Taliban, like my father, who was whipped below the waist and now has problems with his legs,” she explains. “And there is a third type, and they are simply afraid.”

When I quiz Assia precisely what she thinks of the Taliban, she shrugs and responds that she has no thoughts on the Taliban. The young advocate wants to be a diplomat someday, and has no plans to join the hundreds of thousands desperately vying to leave their homeland.

“If women keep fighting like this, we will advance someday,” she says with surprising optimism.

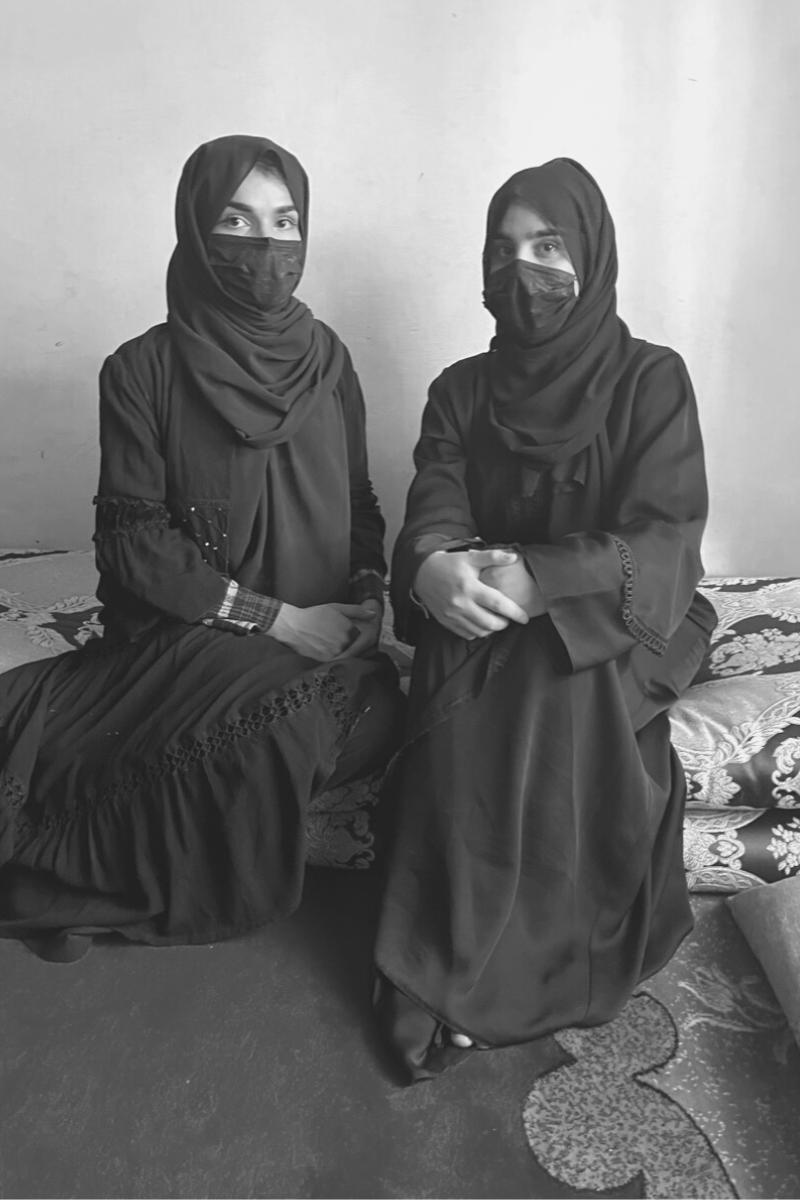

I ask Assia and her activist friend if I could take their photograph from behind. No, the women insist. I must take it from the front. I worry for their safety. Yet their actions assure me that they will not be plunged back into a voiceless, faceless existence.

And even though the markets are still bustling and awash with withered goods, the economic woes since the U.S. froze the Central Bank funding last August have taken a toll. Sadly, women beggars, often with small children and babies crawling in the dirt beneath their feet, have always been synonymous with Afghanistan. Now, it seems that their desperation has reached new heights, with women screeching from behind the netting of their blue burqas, pleading for anything to fill their stomachs.

One afternoon I observe the Taliban patrolling areas thick with the begging and the needy, apprehending those suspected of being part of the criminal enterprises forcing trafficked children to solicit money and allowing those deemed to be in genuine need to still roam the congested streets.

Terrorist attacks, mainly under the guise of ISIS, do happen. But the threat outlook has undoubtedly transformed since the height of the U.S. occupation. For other groups of women, especially in rural pockets – who may never have even seen a foreigner or benefitted from the $2.2 trillion poured into the country – there is the uncomfortable reality that life has probably become a little easier by the plain fact that they don’t have to worry as much about a bomb plunging into their home or stepping on a freshly-planted IED when they walk to their local market.

On a warm Spring Saturday morning, I venture out to Kabul’s Malalai Maternity Hospital. Any probe into the future of women in Afghanistan would be remiss without examining the place where a girl’s life begins and the fragility of the girls and women who bring the next generation into the world.

“There is no change, no problem for us. We walk freely. No one is disturbing us,” notes Dr. Malalai Rahim Faizi, who was appointed Director of the Hospital just over nine months ago – the first woman to be given the Director title under the Taliban.

I am somewhat heartened to hear that the health sector is the one government sector where the Taliban has not imposed restrictions on women being able to work. Still, she underscores her personal wish for all girls in Afghanistan to be adequately educated.

“If they can’t go to school, they can’t reach high and benefit society,” Dr. Malalai stresses.

Nevertheless, the searing reality is that despite the trillions poured into Afghanistan under two decades of a foreign footprint, it remains one of the most challenging places in the world to give birth and be born. A chart that hangs on a Malalai wall shows me that there are an average of 1500 births at this one public Kabul hospital every month. But of those, an average of 41 will be a stillbirth, 18 newborns will die, 57 will require major surgery, 289 will need a lifesaving blood transfusion, and at least two mothers will lose their lives.

Over the past year, the UN and a host of other NGOs have raised the alarm that the health sector risks backtracking even more, with international donor support having been drastically reduced after the fall. Only what those same reports fail to mention is the rampant corruption of the Republic era and that much of the money went into private pockets rather than helping in-need Afghans.

As it now stands, patient numbers at Malalai are rising largely due to more village women being able to travel to the capital on the once conflict-laden roads.

In the ward for “healthy” babies, newborns sometimes sleep three to just one small plastic box, functioning as a makeshift cot. Across in the ward for the “unhealthy” babies, mostly premature souls in incubators are adorned with necklaces of white tubes, little bodies with heaving rib cages heaving for every breath, their crinkled faces carrying the air of old women and men.

“This is very sick,” a male physician tells me. “And the ones that don’t cry when they are born.”

U.S. sanctions and frozen funds might have slashed public funding, and the world’s media may have moved on to other crippling global crises, but not all international donors have turned a blind eye to the country that holds so much of our collective consciousness and memory.

“In the previous government, the budget was given by the Ministry of Finance,” Doctor Malalai points out, adding that when funds dried up after the fall, a renowned NGO, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), swooped in to ensure maternal health would not crumple into devastation. “The food, the medicine, the utilities, salaries – the ICRC is supporting everything.”

Not everyone has forgotten the women of Afghanistan.

Maiwand Naweed contributed to this report.