INTRODUCTION: Our world brims with entrancing, complicated places. But none that quite hold the heart and clutch the imagination like Afghanistan, which means “Land of the Afghans.” It is a landlocked trove of timeworn beryl stones and hidden treasures, of dusty paths encrusted from the historic Silk Road, of black skies with stars that light up the serrated mountain ranges, and mud-walled homes where those with pinched faces and warm eyes eat by candles and moonlight.

Every child born in Afghanistan is a child who comes into life a victim of war. And every parent too often puts those they love most to sleep with the uncertainty that one or all may not rise to the shards of peeping pink light again. It is the place where we journalists venture and immediately fall in love with open Afghan hands, cracked by tireless work and unwavering hospitality.

It is also the berth we go to have our souls shredded into a million pieces every time smoke plumes rise into the muggy sky from yet another bomb, or when a woman weeps from behind a sea-blue burka, unable to feed the baby in her arms.

Afghanistan embraces us and destroys us. Still, we cannot stay away from its gentle call. It is a nation that has long been burned and entombed by outside occupation, by conflict, by poverty, by its own past. Afghanistan’s flaxen plains and clear blue skies have seen too much death. Too many men have taken their last breath while crouched in trenches; too many mothers have gone to the market for honeyed sweets and never come home. Too many Afghans from too many sides have lost lives and limbs in battles of ideology, power, and land.

You can forget it is a beautiful country. A beautiful country beneath the bloodshed, stitched and ripped, stitched and ripped, throughout decades of ceaseless conflict. Let us not forget that Afghanistan is also a country personified by survival, toughness, tender faces, and a zest for something better. Curling around the famous Hindu Kush, Afghanistan remains one of the poorest places on the planet, yet so rich in its generosity. It is the snuggled land where strangers offer you their last piece of bread; lyrical souls guide you through the narrow, clay-caked streets; and time spent fantasizing of something better is always time well spent.

With the Taliban having suddenly resumed power on the sultry Sunday afternoon of August 15, 2021, there was an immediate kinesthesia of the old Afghan world passing, and the new beginning with much trepidation and fear. Nobody in Afghanistan really wants war. Yet war always waits in the grimy shadows of broken things. Nobody can predict what will happen next.

But life, including the book of Afghan life, overflowing with chapters of loss and love and faith and hope, goes on. Throughout this collection, my photographer Jake and I take you on a journey through the country that has shaped our journalistic lives; has taught us what it is to suffer and what it is to overcome.

We guide you through life in Afghanistan during the U.S. occupation, the dizzying government fall, the Taliban ascent amid the chaotic U.S. withdrawal, and into this new chapter being forcefully written by men from the mountains who wear their thick black turbans like crowns.

We accompany you across multiple provinces of Afghanistan in the immediate months after the Taliban, officially termed “The Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,” took hold. There are the tender moments: the afternoons filled with children begging for soccer balls and screeching with delight through the antiquated village roads; the emerald lakes iced into absolute stillness; the devout absorbed in prayers on mats by the roadside, adhering the first call to prayer against hints of light behind the ridges. Then there is the callous side, the war-wracked sentiment, the notion that a Band-Aid was ripped from the bullet wound. The fear for what comes next, the longing many Afghans have to leave, the unraveling humanitarian catastrophe, the hunger pains fused with the ache of abandonment. With the Taliban at the helm, there is much we know, and much that we do not.

However, we must never forget a little girl’s dream to be more than an obscured outline banished to a basement and permitted only to see her world from the netting of a burqa, her existence buried beneath layers of undulating material.

During the Taliban’s rule of the nation between 1996–2001—until they were unceremoniously usurped from power by the United States in the aftermath of September 11—girls’ education was stopped at the secondary level. Their public lives were suddenly severed short. It was clear most would never emerge with a face that could be kissed by sunlight until they were in the twilight of their lives.

The Taliban of 2021 pledges they have changed. In many ways, they have—yet almost immediately into their tenure, schooling for girls stopped, and many women are no longer permitted to go to work if it entails collaboration with a male co-worker.

In those first confusing months, education was not the only thing high school—and some university—girls lost. Tangled within that declaration, they lost their right to a future, to some semblance of autonomy, to ambitions beyond their humble homes.

I have walked through the Ministry of Education—a run-down building with faded white walls and small tracts of greenery rising from cracks in the concrete—multiple times since the Taliban took control of Afghanistan in mid-August 2021. The floors and stuffy office rooms are filled with the new government’s most devout, as evidenced by their long beards and constant twisting of prayer beads, but I have yet to spot a single woman inside the busy halls. It is a sober reminder of the state of girls’ education inside an Afghanistan in limbo, with next to no input from the gender suffering most amid the Taliban takeover. These are the things so many of us take for granted and the things we cannot forget when it comes to fighting for Afghanistan.

On one occasion in Khost, I sit on the floor sipping tea with brave-faced older women and widows who speak passionately about the consequential necessity of female teachers and students. One of the ladies’ small granddaughters—just nine years old—slips quietly beside me onto the cool concrete. She says nothing, her innocent, frightened face and milky eyes staring inquisitively into mine.

I learn that she is already engaged. Her poor parents, made even poorer by the economic crisis gripping the beleaguered country, felt they had no other means but to essentially give her away to an older man in exchange for fast funds, as per the cultural custom that the brides’ families are paid. The wedding will take place after her first period. There is no more education for the timid girl with milky brown eyes; she no longer has a choice. This is not new in Afghanistan, but with the drastic cash shortage, I fear it will become even more commonplace.

We can pontificate all day about statistics and percentages and death tolls and displacement numbers, easily forgetting that numbers have names and names have faces.

Each face has wrinkles that make up a map filled with tragedies to tell. These are the ordinary Afghans who have lost someone they loved most in this life. These are the ordinary Afghans who have no choice but to endure decades of hardship and havoc. These are the ordinary Afghans who supported the United States through two decades of occupation, who nursed the wounded and sacrificed time with their own families for weeks, or months, in the pursuit of freedom and the backing of the American invasion.

Unlike many other conflict-drenched countries I have canvassed, where people work ceaselessly to survive and struggle and yet don’t know that life could be any different or better, Afghans have tasted something else. Something different, something more. Everyone in Afghanistan has lost someone.

Everyone is a survivor. Everyone has a strange story to tell, usually passed on offhandedly as we eat bread and oily rice with our bare hands from plastic mats, our backs against exquisitely patterned cushions.

There is the Mujahideen commander who told me casually about his encounter with Usama bin Ladin at an orange farm in Jalalabad in 1989. There is the witch doctor who tried to heal my woeful food poisoning by flapping his hands. And I will not forget the women who boiled water and lathered my hair with soap when there was no electricity or running water. I will not forget the tribal elder who excitedly demonstrated the best way to fold my new checkered, silk hijab as the Taliban waited to take me away.

When I go to sleep most nights, I wonder what is, and what will become, of the flimsy Afghan dream born in the time of the American-led war.

Two days before much of the nation’s north fell to Taliban rule, I met a thin boned, bubbly young Afghan man by the name of Noorzai Ibrahimi. He is one of Afghanistan’s top skateboarders—having gone from a beggar boy in the streets offering to weigh people with his cracked scale to learning how to wheel and flip and fly.

Noorzai is a long and dear friend of Jake’s, who had plucked him from child poverty and taught him to skateboard years ago. He is twenty and madly in love. He laughs at the end of every sentence. But in the height of the maddened airport evacuation, Noorzai had to flee his homeland, his family, and his desires, or else his beloved boarding would have been rendered a thing of the past.

Small things. But small things matter inside the Afghan dream.

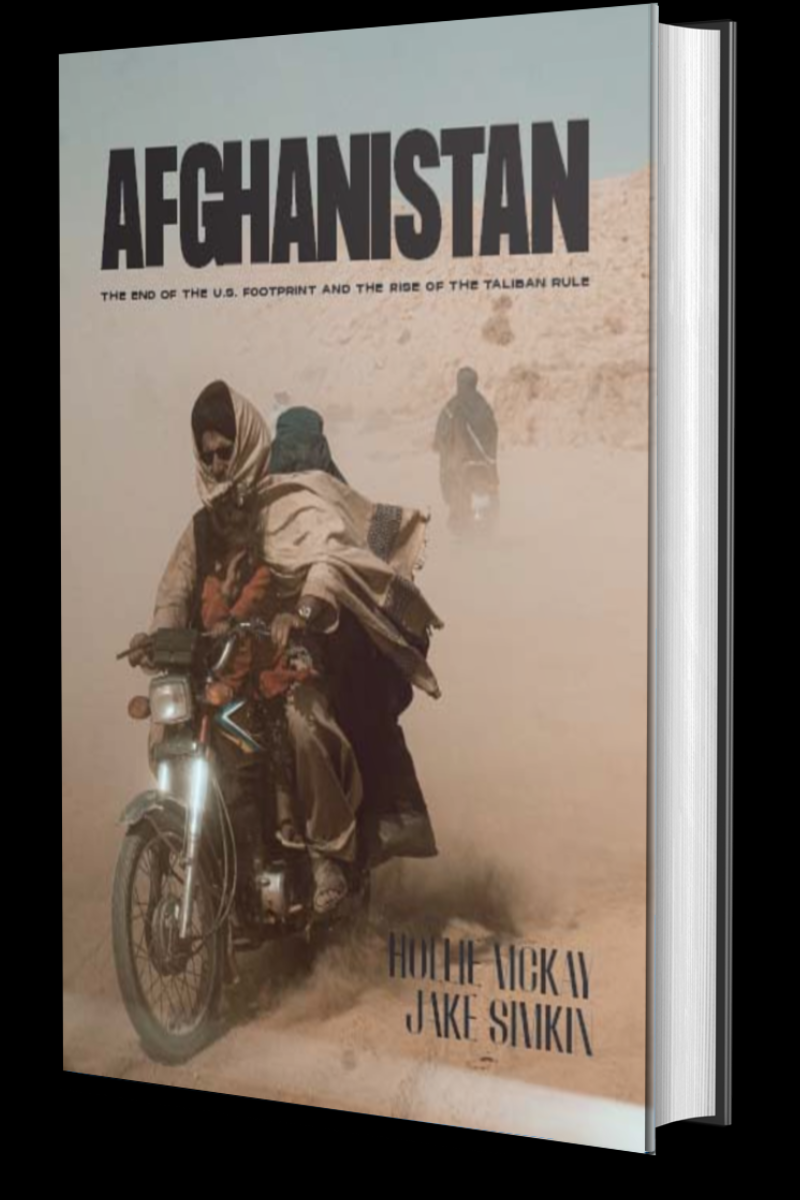

My written and visual coffee table book collaboration “AFGHANISTAN: THE END OF THE U.S. FOOTPRINT AND THE RISE OF THE TALIBAN RULE” with renowned war photographer Jake Simkin is now available here.