GUANTANAMO BAY, Cuba – A clean-shaven detainee with a short haircut, dark jeans and a light buttoned-down shirt meanders into the brightly-lit, windowless courtroom – reminding me of a penchant child summoned to the principal’s office.

He is short in stature. His face is etched in exhaustion with body language that seems to scream out, “so over this charade.” Irrespective of where you stand on the matter, it is hard to blame him. This is Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, prisoner number 26, a Saudi citizen of Yemeni descent and accused mastermind of the 2000 al-Qaeda-operated bombing of the USS Cole in Yemen. Nashiri has been in U.S. Custody for two decades with a fate still far from determined. Despite the passage of time, the case remains in a drawn-out, pretrial stage.

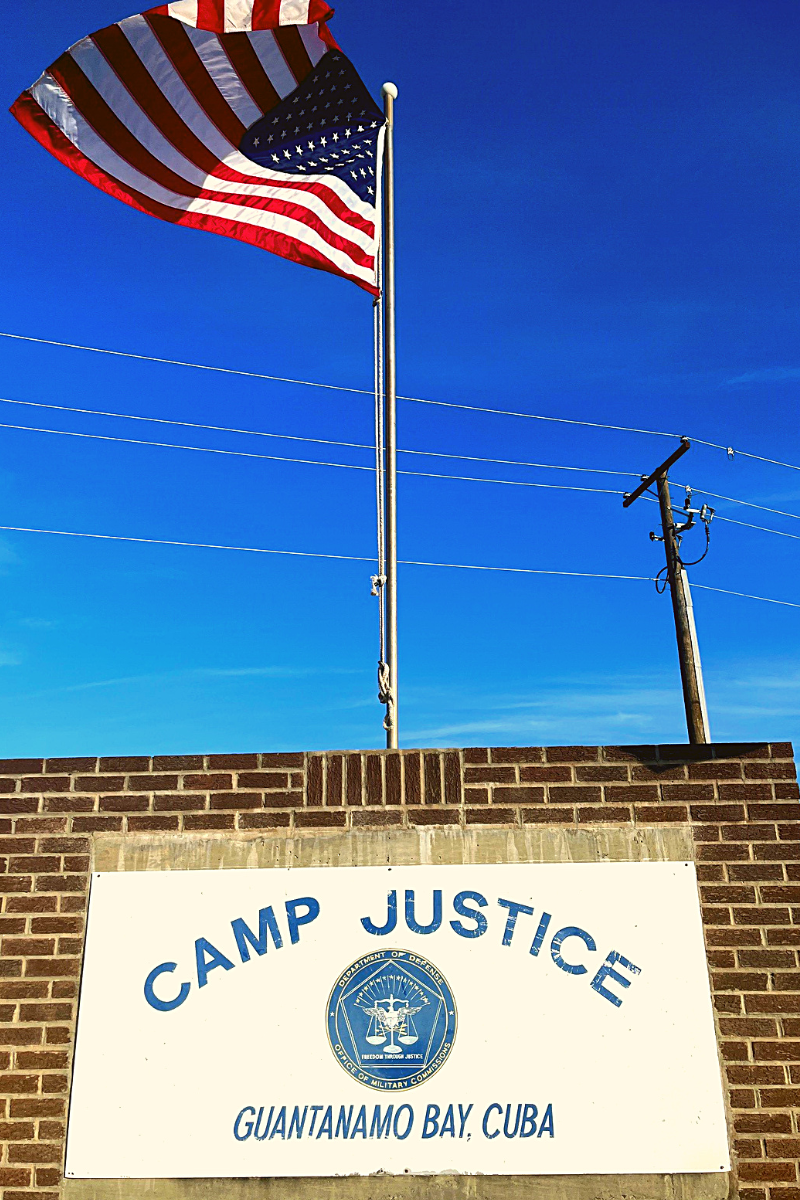

Welcome to Camp Justice at Guantanamo Bay, the notorious pocket carved out on the Cuban island, centered around the faded yellowish building on a small hill on which an American flag flies high into the stark blue sky above. Guantanamo, also referred to as Gitmo or GTMO, is known globally as home to a dwindling number of foreign nations alleged to have been the “worst of the worst” terrorists swept up in the bitter and uncertain aftermath of the September 11 attacks.

Nashiri, now 57, is charged by the United States government with “perfidy, murder in violation of the law of war, attempted murder in violation of the law of war, terrorism, conspiracy, intentionally causing serious bodily injury, attacking civilians, attacking civilian objects, and hazarding a vessel.”

He faces the death penalty. The other case in which capital punishment is on the table is that of the five men indicted for planning the 9/11 attacks. In many ways, the brutality of Nashiri’s alleged actions as an al-Qaeda operative has been overshadowed by September 11, falling into the dark hole of a continuous news cycle.

Four uniformed Army personnel – two women and two men – remain close by as Nashiri greets his defense attorney, Anthony Natale, with a wide smile, handshake, and tight hug. Nashiri politely acknowledges the handful of officials as they enter the room with a slight nod. He twists his body in a kind of feeble effort to stretch, tests his translation headphones, and waits calmly for the Judge to enter the largely empty room adorned with wooden desks and black chairs and flaccid flags representing each of the U.S. military branches.

After passing through multiple TSA-style security checkpoints, I’m sitting in the back of the cold, triple-paned glass-encased viewing gallery beside a couple of American law school students, referred to as “NGO observers.” I am watching the hearings both in real-time in front of me and then with a forty-second delay on the monitor above, giving the intelligence community the chance to cut the sound should classified information be raised.

A sign on the wall cautions viewers not to draw, sketch, doodle, or risk being reported to military police. A standard verbal disclaimer read by a military police officer before the commencement also warns us not to sleep or behave in any way that could be construed as disrespectful.

A constant swivel of Nashiri’s office chair reflects the detainee’s frustration with the elastic judicial process echoed by much of America. When a mid-morning recess is called, Natale requests permission on behalf of Nashiri not to return to the pallid courtroom for the remainder of the day, a request the Judge promptly grants.

Much of the week’s pretrial hearings – intended to address any issues and simplify them so that the trial if held, will proceed smoothly – are comprised of witness testimony from a remote Virginia hearing room (RHR) not far from the Pentagon. These hearings are a hybrid model of here and there, with some prosecutors and defense attorneys litigating from afar and others choosing to come and go from the Guantanamo courtroom. The testimonies this week come from former U.S. government officials tasked with investigating the deadly assault long ago.

I stare at Nashiri and back at my notes, containing the names of the dead. With time, a situation tends to become less traumatic, its ache receding from collective memory. We no longer see the victims –sailors aged between 19 and 32 whose lives were cut searingly short in service of their country. Instead, we see portraits of aging alleged terrorists, who over time appears harmless, wrapped in international concerns over human rights abuses and due process.

Before coming to the Guantanamo Naval base in early August, I asked many friends and associates about their memories of the USS Cole attack. Those outside the middle-aged military sphere had vague recollections at best. Even in the line of duty, many I encountered were either small children or not yet born when the millennium changed, and the incident occurred.

Let us remember.

Almost a year before al-Qaeda struck the Twin Towers, on October 12, 2000, the same terrorist outfit deployed suicide bombers to the U.S. Navy destroyer refueling at a port in Yemen. The operatives, who approached the vessel in a motorboat, unleashed some 700 pounds of explosives, killing 17 U.S. sailors, and gravely wounding another 39 crew members, leaving behind a 40-foot gaping hole in the ship’s side.

Born in the revered Saudi city of Mecca in 1965, Nashiri, who would have been 35 at the time of the onslaught and considered a close confidante of Usama bin Laden was later identified by U.S. investigators as the ultimate mastermind and head of al-Qaeda operations in the Arabian Peninsula. In addition, he was implicated in the bombing of the French-flagged, Malaysian-chartered tanker Limburg, which was transporting Iranian crude oil in 2002. One Bulgarian crew member died.

Nashiri was apprehended by the CIA while living in Dubai in the late fall of 2002. He spent some 46 months as a “high-value detainee” shrouded inside CIA “black site” detention facilities spanning Afghanistan and Morocco to Thailand, Poland, and Romania. He was transferred to Guantanamo in 2006.

It has been almost 22 years since Nashiri was first taken in by the U.S, 16 years since they brought him to Guantanamo Bay and nearly 14 years since the first slate of charges against him. So why on earth hasn’t this moved forward further?

As per cables released due to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) lawsuit, Nashiri was at the very least waterboarded, beaten, and confined in a crate while in black sites. At a 2007 military court hearing, he referred to previous confessions of involvement in the USS Cole onslaught as being under the duress of torture. Nevertheless, Nashiri was charged the following year.

Then, just two months later – amid intense outcry following the exposure of the “enhanced interrogation techniques” program and a subsequent U.S. Senate investigation – the Obama administration ordered the charges dropped. They were reinstated in 2011, and the case remains in pretrial proceedings.

From my outside eye, it appears that many fault lines have been hindering the process in recent years.

The court spent much of a whole day on taxpayer dime deliberating whether one member of Nashiri’s defense counsel, Capt. Brian L. Mizer of the Navy who is the lead military defender – and first requested to leave the case months ago – should be granted his request to withdraw over an alleged conflict concern. Mizer previously represented another former Gitmo detainee and accused driver of Usama bin Laden, Salim Hamdan, who was implicated for his involvement in the USS Cole attack. A statement from Hamdan, who is in Yemen serving his sentence, will potentially be proposed by the prosecution.

Nashiri, speaking Arabic and appearing wide-eyed and broken as he addresses the Judge, requested Mizer – who he had evidently established a strong rapport with – remain on his case yet stated that the conflict with Hamdan was “unacceptable.” Hours on, with much back and forth, the matter is not resolved. It all speaks volumes of the frustratingly slow yet careful legal adherence that makes up the bogged-down commission. Natale assures me that there are easy ways to resolve it, but nothing seems easy in the complex legal system.

For example, in 2014, the Judge dismissed the charges pertaining to the Limburg bombing, generating an appeal by the U.S. government. More back and forth ensued over violations of the Appointments Clause concerning the Military Commission Review (CMCR).

The Cole case was again derailed in 2017 after the defense counsel discovered microphones in attorney meeting rooms (the government contended the devices were old and inoperable), which triggered the departure of Nashiri’s civilian team on “ethical grounds.”

In 2019 the D.C. Circuit Court tossed out over two years’ worth of decisions issued by the then-governing military Judge, Air Force Colonel Vance Spaeth, over conflict of interest for failing to disclose he was seeking a position as an immigration judge. Judge Army Col. Lanny Acosta, the fourth Judge since 2011, who is still on the case and is now also the chief Judge of commissions, subsequently took the reins.

And then came the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic at the beginning of 2020, which halted proceedings for many more months to come and saw the February 2022 Acosta had set as a trial date wither away. Even now, when one person in the room tests positive, hearings are stalled and suffer additional lags.

But despite the delays, the stop-start legal proceedings, and the continuing uncertainty, the root of all this lies in the use of torture or “enhanced interrogation” techniques (ETIs). A heated debate rages over what can and cannot be used in court, which is made even more difficult by the intel community’s efforts to conceal sensitive identities.

Indeed, mistreatment claims have become the ghost of the past that will not stop haunting, providing a critical line of defense for arraigned terrorists and high degrees of sympathy for the detainee not only in the United States but worldwide. Such methods emerged in the angry aftermath of September 11, in a wounded and worried nation determined to do whatever was necessary to curb the next threat. It doesn’t make it justified, yet context still matters.

Nashiri’s defense – and much of the global human rights community – contend that he has been diagnosed as suffering from long-term post-traumatic sense disorder and depression due to the years spent under the thumb of controversial interrogation modalities.

Nashiri has also been diagnosed with the psychiatric condition of “learned helplessness.” This means that the defendant lives in a perpetual state of “learned helplessness,” characterized as a mental state of powerlessness, of telling holders what they want to hear.

In a surprise move in May 2021, Judge Acosta resolved to consider information gleaned from CIA “cruel, inhumane, degrading treatment” torture sessions in the pretrial hearings, marking the first time prosecutors have been given the green light to use such material. In February 2022, the defense filed AE 469, a classified Motion to Suppress Statements Reflected in Detainee Information Management System (DIMS). Over the past weeks, lawyers for Nashiri have kept up a steady drive or the prosecution to be forbidden from using the admissions made by their client all those years ago.

On August 8, Judge Acosta responded with a ruling that the prosecution seeks to use around 5000 government documents but failed to specify which ones it would introduce. The Judge ordered the prosecution to disclose by September 15 the DIMS citations it intends to present in its case-in-chief. The defense has until November 1 to submit a motion to suppress statements it alleges were obtained involuntarily. Critics have likened the move to the government rewarding and incentivizing torture.

Moreover, the defense has kept up a line of questioning that suggests inappropriate coordination between the CIA and authorities who directed later interrogations inside Gitmo. Their strategy purports to cast doubt on whether the government even had the right person when conducting interviews inside Yemen, or has subsequently made a worthy attempt to track them down for verification more recently. It underscores the notion that investigators never independently verified passports, fingerprints, and licenses, planting the seed that individuals could have potentially been coerced or threatened by Yemeni officials to provide false testimony.

From Natale’s purview, the standards of information gathering should not be diminished for cultural reasons.

Still, this points to the challenges American law enforcement has in probing cases on sovereign soil, whereby it insinuates that it cannot demand such things as biometric data of the citizens of a foreign nation. They know who they are speaking to, and so do we, but without definitive proof, can it solidly hold in the court of law? In large part, those uncomfortable factors have attributed to why detainees were brought to Guantanamo in the first place but have since been clouded by the stain of interrogation tactics.

The use of ETIs also means that the press, NGOs, and, most importantly, the family of victims are not privy to the full spectrum of what happened before, during and after the USS Cole attack. The monitors are on occasion severed into the static mode, and closed sessions are routinely called for secret testimony. As participants in classified sessions require high levels of security clearance, defendants in military commissions are also left in the dark.

In its defense, the intelligence community does whatever it can to safeguard personnel who may or may not still be employed in classified positions. However, Natale tells me he doesn’t care about names. He maintains that “what they did and when they did it” is crucial, insisting that tapes have been destroyed and the hypocrisy of the U.S. abhorring other countries for the use of torture despite its track record is tragically flawed.

Nonetheless, Judge Acosta makes a point of urging lawyers to carefully review their material as he wants to “avoid a closed session and keep proceedings as transparent as possible.”

Thus, much of the open witness testimony has come from special agents operating under the umbrella of government wings other than the CIA – the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS) and USAF. Witnesses reiterate the general notion that statements derived were more like “conversations” or “interviews” than intense interrogations.

One Special Agent Lange affirms that in 2007 Nashiri was “very excited” to talk to her three-person investigation team in Gitmo and that he claimed to have been paid $50,000 by bin Laden to orchestrate the deadly USS Cole attack. She also vows that there was no indication of recent maltreatment and that the detainee was “pleased” to have been moved to Guantanamo and finally put in an official system.

However, one of the most significant issues I see in how and why the Guantanamo judicial procedure has spiraled into being widely touted as a “black eye” on everything the U.S. ethically stands for is the government’s unwillingness to put forth their side of the story. I am forewarned that almost all journalists’ requests are denied. In lockstep, the written response I received is that the Office of the Chief Prosecutor “respectfully declines your request to interview any member of the Nashiri legal team.” The U. S’s legal lineup is led by Mark Miller, an assistant U.S. attorney from the Department of Justice who previously worked on homicide and sexual assault cases in the New Orleans federal court.

By contrast, Nashiri’s top attorney Anthony Natale – a well-heeled capital defense attorney, employed by the Pentagon– is charismatic, open, accessible, and equipped with information. He formerly represented designated “enemy combatant” Jose Padilla, who was convicted in a federal court in 2007 of conspiring to commit murder and fund terrorism. He is slated for release from Colorado’s Supermax in 2026. The importance of the court of public opinion and transparency is not lost on Natale, and the defendant is certainly not deprived of a top-tier attorney.

The Florida-based attorney sits down with me after court one afternoon. He lists a litany of understandable grievances with the commissions. There is the disorganization of a legal system in which the U.S. Constitution does not apply, the logistical quagmires of having to fly on limited flights to Gitmo to meet with his client and then go through yet another approval process.

Occasionally, he says, access to his client is denied without reason. Still, Natale pegs most of the problems and the sluggishness of proceedings to ominous interrogation methods.

“He (Nashiri) is coping, despite the absence of proper treatment given to the damage that was done to him,” the lawyer, who is embraced by his client each time they enter court, says. “But he is extremely grateful for the representation, for so long no one treated him as a real person.”

Nevertheless, U.S. military commissions – a type of military tribunal established to try individuals for “unlawful conduct associated with war” – are not new. For centuries, they have been used to prosecute “enemy combatants” for breaches in the laws of war.

Such commissions have been in place since the Revolutionary War times of 1778, resulting in the hanging of a British messenger convicted of spying. The model went on to have a presence through the two-year Mexican American War beginning in 1846, the Civil War sixteen years later, both World Wars in the first half of the 20th century and the decades that followed through today.

Per the updated Military Commissions Act of 2009 (conceived in 2006, reformed three years later and amended in 2011 and 2013 to give greater protections to defendants), a Convening Authority is appointed by the U.S. Secretary of Defense. The commissions amalgamate U.S. federal criminal courts and the military court-martial system.

I ponder where things stand now, not only in Nashiri’s case but in the opaque and odd Cuban island of Guantanamo Bay. Over the past twenty years, some 780 detainees have been held inside the base’s military lockup. Today, just 36 men remain. The Military Commissions have convicted just two.

Most analysts I speak to speak of the increasing likelihood of plea bargains to finish all the cases. It is unclear where the individuals would complete any remaining sentences and even if their home governments – including Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Pakistan, Somalia and Kenya – would be open to or even trusted to take them back.

Multiple U.S. administrations, apart from President Trump, who sought to fill the garrison with “bad dudes,” tried unsuccessfully to close the facility. However, as I drive through Camp Justice on a sweltering summer day, I see the shells of brand new “box homes” springing up on arid land. More money to the tune of many millions is now being spent on the chance that any of the remaining cases will go to trial, requiring a great deal of housing and tents for legal staff, witnesses, attorneys, NGOs, and the media. Multiple dates have been earmarked for selecting at least a dozen U.S. military officers as jurors in a potential Nashiri death-penalty trial.

No one can say for sure what will happen next, although the likelihood of the case moving to trial is shrouded in speculation. Nevertheless, critics persistently raise the red flag over the commission’s plunge into dysfunction, an embarrassment to America’s standing as the planet’s leading advocate of human rights.

However, it is possible to appreciate the work of all sides in the commission equation while lamenting the elongated nature of the proceedings. Yes, the process is painfully slow and comes at a high cost to the United States taxpayer. (Together, we have spent around a billion dollars housing and trying suspects from across the globe. The yearly cost to U.S. taxpayers per Gitmo detainee is around $10 million, while the cost of keeping a prisoner in a U.S. maximum security federal prison is approximately $78,000.)

Natale darkly jokes that he isn’t sure the case will conclude in his lifetime but remains committed to the fight.

Yet those who pay the highest price for the process are the victim’s families. So, when we remind ourselves that justice has not been served for the accused, let’s not forget that justice has not been served to the families either. But, again, this appears to be largely due to the fallout of the controversial ETI program.

“This has done a disservice to the survivors, the victims, and their families,” Natale stresses, adding that he encourages them to reach out to him, to yell at him if need be, and wishes more would engage in what from the surface seems an uncomfortable alliance.

But from my own perch, as someone who has witnessed a multitude of criminal proceedings in various pockets of the planet, most recently in Iraq, whereby accused ISIS terrorists are sentenced to death in a matter of minutes with little access even to an intimidated court-appointed defender, it’s hard to mentally equate the legal transgressions of Guantanamo to much of the terrorist-laden world. Admittedly, the Commissions are far from perfect and wincingly slow. Yet whichever way you slice it, they are moving along.

Part of the journalistic struggle is to see the situation from all sides, not to take sides, and not allow the passage of time to dim context.

A liaison to the victims who works for the prosecution permits family members of the fallen and surviving crew members to watch the pretrial in a reserved section of the back galley. Just one family member sits in the glass-sheathed galley, watching and waiting, stepping out into the burning sunshine for small breaks.

Somehow, someday, they need to see justice – whatever the outcome – for what was done to the person they loved most in the world. The story of Nashiri is a small one embedded in a much larger and messier one. The big picture is the rocky road toward closure for those who have been left languishing for 22 years.

It is easy and correct to note that Camp Justice reeks of the scent of fumbling and wasted money, but the only path forward is forward. Faith in our democratic institutions can only be clawed back bit by bit, case by case.