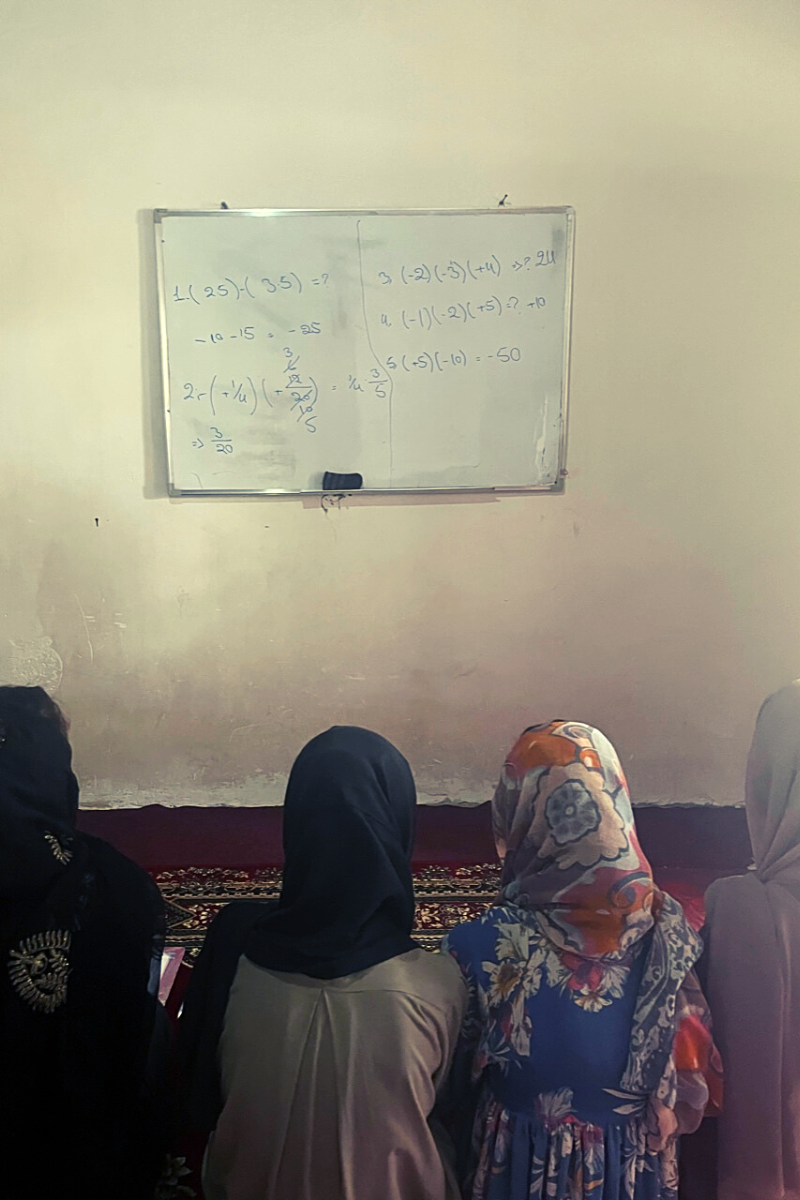

KABUL, Afghanistan – Down a narrow, cobble-stoned hill in the suburbs of Kabul, rows of young women wrapped in ebony and floral hijabs stare intently at mathematics equations on a whiteboard. Only this isn’t a proper school. This is a family home – a home that almost four months ago became an underground school desperate to learn more than a year after Afghanistan fell back to a Taliban government.

“These girls cannot make public they are going to study, so they go under the name that they are going to the madrassa (mosque),” Monesa Hamedy, a 23-year-old who months ago set up a cost-free school for about 28 girls aged between 14 and 19 in her simple family abode.

The Taliban’s halt on girls’ secondary education is seen as a glaring reversal for the country, which already endures one of the world’s highest female illiteracy rates. While there are a handful of provinces, mainly in the less conservative pockets in the country’s north (including Herat, Kunduz, Faryab, Jawzjan, Badakshan, Mazar-e-Sharif, Zabul, Samangan and Sar e Pul) that allow girls to attend classes as they did previously, for the vast majority, school has become an absolution that seems as though it might never return. (It should be noted, however, that the suspension is on public schools, many secondary private schools across the country continue to operate).

The likes of Monesa could not stand idly by. So, in the early 2022 summer, she took matters into her hands. The ad-hoc, clandestine school is just one of many quietly cropping up across the war-recovering Afghanistan.

The students learn everything from biology and chemistry to physics and mathematics, with Monica’s immediate and extended family contributing their knowledge to an oversized book filled with hand-written equations to help the girls learn and as a symbol of unwavering support.

“I bought books with my own money to provide for the students coming here,” she declares proudly.

Up until recently, Monesa was studying Turkish literature at Kabul University. However, she was suspended from class for wearing a thin brown hijab rather than a thick black one. After making a video about the incident that went viral, she says the Taliban expelled her. Since then, Monesa has been studying at a friend’s bookstore and alternating teaching days with her 18-year-old brother, Abdullah, who is in his first year studying economics at university.

“Education is the obligation of every man and woman,” he states, his face creasing. “My oldest sister taught us, my brothers and me, everything. So, it is all due to her that we are at this level now.”

An array of petite, fine-boned students come by to tell me their stories. Outside, in a world run by men, these youthful voices might be relegated to the shadows – yet they rebuff the constant weight of hopelessness that is a girl’s life in Afghanistan.

Beheshta, 17, says that she did not miss a beat by studying at home even before coming to the underground school. Basra, 14, underscores that her favorite subject is geography and that she won’t give up on the battle for equal educational rights. And Suna Mohammadi, 16, loves math the most but dreams of being a news anchor in the future.

Other girls and women have taken to online education as a means of empowering self-study, but that isn’t tenable for the large and impoverished parts of the population without reliable wi-fi and a steady stream of electricity.

Since last September, in the searing aftermath of the chaotic U.S. withdrawal after two decades of war, the education embargo has ignited international outrage and sanctions. It is one of the jarring reasons no country is yet to officially recognize the Taliban government, formally termed the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.

And even though I have covered the issue of girls’ education and their altered lives repeatedly in months and years past, there is always that one epiphanic moment. The one moment that grips your heartstrings and doesn’t let go, the moment you realize – really realize – just how important this issue is. As a westerner, it is a privilege that I haphazardly took for granted for too long.

On the last Friday morning of September, more than fifty minority Hazara school girls – and some boys – were slain in a brutal terrorist attack as they sat for a practice university entrance exam inside an educational institution. Two days later, the girls who had survived, the girls who lost their friends and sisters and those they loved most in the world – all while wailing and trembling in grief and trauma – lined up outside that butchered schoolhouse. Each of them carried schoolbooks in their slender arms, demanding the Taliban let them inside to learn.

Girls and women are always the soft targets in conflict. As has long been the case for the persecuted Hazaras, Afghanistan feels like a place where you can only live on luck. Each girl appears sad and wise beyond her years.

And I never stopped being shocked by both hardship and resilience.

Their brazenness on this day is as laudable as it is tragic. Two weeping Hazara girls refuse to leave the gate until the Taliban guard reluctantly agrees to let them inside to collect their textbooks. At the very least, they wanted to be at least able to study at home, not knowing when the learning center would re-open. Clutching each other, I have never seen two girls sprint so fast. Education is not just a hobby to them; it is everything to them: it is their past, their present, and the future they had to hold on to.

Officially, the Taliban says they are working to open secondary schools for girls as soon as possible, but there is no timeline. Afghanistan is the only country in the world with prohibitions on girls’ education, as there is no mandate for this in Islam. Instead, extremists paint this as akin to the Pashtun culture’s traditional customs.

However, in the dozens and dozens of conversations I have had with the top echelons of the Taliban since their return to power last year, not one publicly concedes to agreeing with the protracted ban. Some even encourage journalists to write about it to keep up the public pressure.

One source explains it succinctly: 99 percent of the Taliban aren’t against women working or education, but it requires them to “upset friends who have fought with them for 20 plus years.”

The sense is that one percent of hardliners are calling the policy shots. With the Emirate likely to maintain a firm grip on power for the foreseeable future, it remains to be seen how long the girls will have to battle for the quest to learn from the depths of a dank basement.

Maiwand Naweed contributed to this report.